Portion of Shroud of Turin.

Some people see small, round, raised, objects over each eye, purported to be coins, on this isplay of three-dimensional information encoded in the face on the Shroud of Turin. The original source is probably Prof. Giovanni Tamburelli of the Centro Studi e Laboratori Telecomunicazioni S.p.A., Turin, Italy.

Before getting into the debate as

to whether there are two coins of Pontius Pilate discernible over Jesus’ eyes

on the Shroud of Turin, I would like to propose a new thought, that I don’t

believe has been mentioned yet. Why on earth would Jesus’ friends have used

coins of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judaea who in Luke 23:24 “gave

sentence that it should be as they required [crucifying]”? The citizens of Judaea had good reason to

hate Pilate. Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – c. 50 CE)

described Pilate’s rule as being full of “briberies,” “insults,” “abuses,”

“repeated killings without trial,” and “supremely grievous cruelty.”

Jews also had good reason to hate

Pilate’s coins. The coins issued during Pilate’s administration featured pagan

symbols—a small ladle (simulum) used for libation in a religious ritual, three

ears of grain in a metal tripod used by Roman priests, and a curved staff

(lituus) used by augurs to predict the future. Nikos Kokkinos (The Prefects of Judaea, presented at the

2010 International Conference on Judaea and Rome in Coins, 65 BCE – 135 CE)

writes: “… the symbols displayed on the coins attributed to [Pilate], are

surprisingly foreign to Jewish culture and must have left a bad taste. If,

indeed, they had wanted to cover Jesus’ eyes with coins they had many

alternatives to those of Pontius Pilate. The coins issued by his predecessor

governors featured designs that would not have been objectionable to the Jewish

citizens—palm tree, palm branch, laurel branch, ear of grain, cornucopiae,

lilies, vine branch, and amphora. And the earlier coins issued by the Herodians

and Hasmoneans (Maccabees) were also in circulation in the time of Pontius

Pilate.

The variety of Judaean coins in circulation at the time of Jesus’ burial is confirmed in an article "Jason's Tomb" in the Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1967), pp 61-100 written by L. Y. Rahmani who excavated this tomb in Jerusalem in 1956. In this tomb, which had been used over many years, Rahmani details finding a number of bronze coins. Five of these were from the Hasmonean period, two were from the Herodian period, and forty-six were from the time of the Prefects and Procurators, including seven coins issued during the governance of Pontius Pilate.

Pictures courtesy of Jean-Philippe Fontanille

Let

us now consider whether the ancient Jews actually placed coins over the eyes of

the deceased.

On http://www.shroud.com/lombatti.htm

Antonio Lombatti states that:

“[Proponents

of this theory] have always quoted two historical sources: the first is

A.P.Bender, 'Beliefs, Rites and customs of the Jews, connected with death,

burial and mourning', quoted in Jewish Quarterly Review 7 (1895), pp. 103-226,

and the second R. Hachlili, 'Ancient Burial Customs Preserved in the Jericho

Hills', in Biblical Archaeology Review, 4 (1979), pp. 28-35. Bender, however,

speaks about some Judaic customs of the 19th century and about some Russians,

who used to put coins on the eyes of the dead, while Prof. Hachlili refers to

having found two coins inside a skull of a defunct. Hachlili, however, has

never affirmed that the coins were on the eyelids of the dead, or that it

represented the typical Judaic burial custom of the first century. Therefore

there does not exist an historical source to affirm that in Jesus' time in

Palestine some Jews practiced such rites on corpses.

“In 1980 the

greatest specialist in Judaic cemeteries, Prof L.Y. Rahmani, Director of the

Jerusalem Museums, entered the debate with an article in Biblical Archaeologist.

He rejected without hesitation the idea of a Judaic custom of putting coins on

the eyelids of the dead. Prof. Hachlili, also writing in Biblical

Archaeologist, then immediately confirmed that the tombs she found in 1979 were

in bad condition. The two coins she found in a skull were of the time of

Agrippa (40-45 AD), but the ossuary was full of piled-up bones, the ossuary was

no longer intact, and it was not absolutely clear that the two coins were on

the eyes of some dead person inside the tomb. In short: the coin theory has not

the slightest archaeological support.”

If indeed, there was the practice in Jesus’ time to place coins over the eyes of the deceased, and if his friends chose to use coins issued by the man who had condemned him to death and who was hated by the Jews, let’s look into the physical evidence.

In a letter published in World Coin News (March 2, 1982), Wilburn Yarbrough, Secretary-Treasurer of The Atlanta Center for Continuing Study of The Shroud of Turin, wrote:

“Fr. Filas first proposed his solution to the identification of the coins on the Shroud [of Turin] in October, 1978 at Los Alamos, N.M., at the Shroud of Turin Researc Ptoject (S.T.R.P.) meeting. When S.T.R.P. did not accept his theory, he resigned from the group. The overall view of the scientists is that the letters Fr. Filas sees is a weave pattern of the cloth. This opinion was expressed by Eric Jumper, Vernon Miller and Don Janney at the S.T.R.P. meeting held in Groton, Conn., in October, 1981. There Vernon Miller showed four slides of the eye areas taken in Turin in 1978. These slides did not show and indications of Fr. Filas’ ‘CAI’. In my own research, I came to very much the same conclusions that Mel Wacks did in regard to Fr. Filas’ articles.”

And here is the article that appeared in the January 12, 1982 issue of World Coin News, containing Mel Wacks’ rebuttal to the theory of Father Filas:

Controversy

Continues on Shroud’s Coins

The coin image on the Shroud of Turin Could

not possibly have been made by a coin issued by Pontius Pilate, contends Mel

Wacks, Biblical numismatist.

Originally printed in World Coin News, January 12, 1982

The image [on the Shroud of Turin] was proclaimed a coin of Pontius Pilate by Fr. Franics Filas, S.J., of Loyola University in Chicago, Ill. The subject of that discovery was carried by World Coin News in an extensive article last year.

Wacks is editor of The Augur, official newsletter of the Biblical Numismatic Society, and numismatic consultant to the Magnes Museum, Berkely, Calif. He is author of The Handbook of Biblical Numismatics and has written over 100 articles on the subject.

Background

The Shroud Coin Theory can be traced back to the computerized image enhancement analysis made of the Shrouald photographs by Dr. Eric Jumper, Dr. John Jackson and Kenneth Stevenson Jr., published in the American Numismatic Association’s The Numismatist in 1978. These investigators wrote:“One of our investigations … surprisingly revealed objects resting on the eyes—objects which resembled small disks or ‘buttons’. Could these two objects then be coins? When we mentioned our coin theory to friend Ian Wilson, he, being somewhat of a coin buff, immediately looked into what coins might have been used if the Shroud was genuine. The result of his study produced the possibility of a Jewish bronze lepton of Pontius Pilate minted from 29-31 AD. Additionally, the observation of what appears to be a backward question mark on the object on the left eye seems to correspond to the striking (Augur’s wand) on a lepton! Intriguing points, but to date still inconclusive.”

In 1980, Fr. Filas privately published a 7,000-word study, “The Dating of the Shroud of Turin from Coins of Pontius Pilate,” in which he claimed the detection of curtain features on the Shroud coin image:

“The (letters) UCAI angled from 9:30 o’clock to 11:30 o’clock around the curve of an astrologer’s staff called a Lituus (or Augur’s wand).”

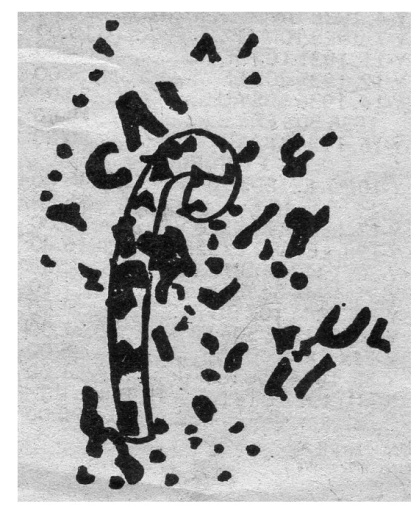

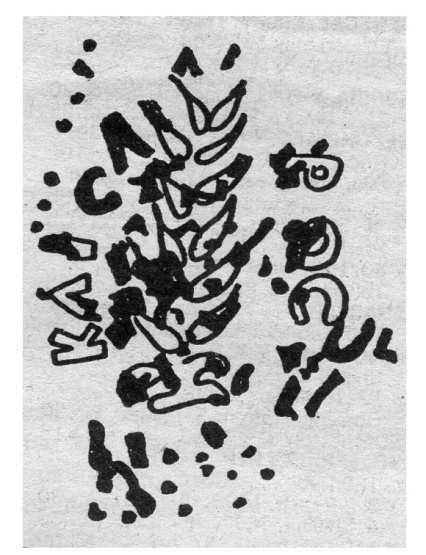

The coin image of the Shroud has the lituus superimposed in the position indicated by Fr. Filas. Wacks maintains that the letters CA are in the wrong position.

Filas goes on to state that the letters UCAI are the portion of the coin inscription TIBEPIOY KAICAPOC. Then, in a display of probability theory, it was shown that the odds were one in six million times a trillion times a trillion times a trillion that the lituus and UCAI are fallacious patterns on the weave of the Shroud, accidentally duplicating markings on the coins of Pontius Pilate.

Misspelled Coins

In a notarized statement, dated Aug. 31, 1981, that accompanied the press release, Filas describes this “missing link” as follows:

“This coin has the vertical lituus (astrologer’s staff), with the letters still discernible beginning at 9 o’clock along the staff of the lituus. The letters are: I, O, then an apparent U eaten away at 10 o’clock. At 10:30 o’clock the letter C. At 11 o’clock the letter A eaten away almost to the surface of the coin, but with visible stilts and crossbar in relief, in high-resolution photography. At 11:30 o’clock the Greek letter iota (I) at the upper half of the line.”

The normal TIBEP and not CAI as pointed out by Fr. Francis Filas, S.J., is outlined here by Mel Wacks.

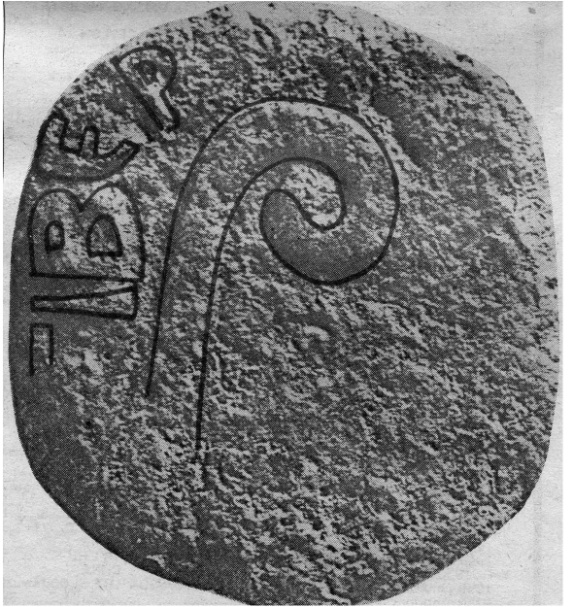

After careful examination of greatly magnified glossy photographs of this coin, supplied by Fr. Filas, Wacks has concluded that “the actual inscription is quite normal for the coin and bears no similarity to Filas’ findings. The visible letters are simply the bottom two-thirds of the inscription IBEP, a portion of the emperor’s name—TIBEPIOY (Tiberius). Both the location of the letters and their shape make this conclusion certain.”

Fr. Filas issued another press release on Nov. 16, 1981, which proclaimed that “Second rare Pontius Pilate coin definitely confirms previous coin imprints on Shroud of Turin.”

Wacks also examined enlarged glossy photos of this second coin and agrees that the spelling is incorrect, appearing as CAICAPO. Wacks goes on to indicate that misspellings were not uncommon on the small bronze leptons which were generally crudely struck in ancient Judea over a 200-year period (circa 103 BC to 59 AD).

However, Wacks went on to say that “the location of these letters are normal for this coin—1 o’clock to 5 o’clock. They are on the right side of the lituus and not in the upper left position of the Shroud coin image. In fact, I know of no Pontius Pilate coin with the letters UCAI in the relative position of the Shroud coin image! None is shown in the collection of the British Museum, nor in the newly published Sylloge of the Collection of the American Numismatic Society, cataloged by Ya’akov Moshorer. Admittedly, there is a drawing of such a coin in Madden’s 1864 History of Jewish Coinage, but most of that coin is struck off of the flan and, in any case, it is only a drawing and may have been in error as other drawings in this book have proven to be.”

Wacks believes that “until someone can produce a coin of Pontius Pilate with the spelling error and with the letters in the position shown on the Shroud (at least approximately), then nothing has been confirmed as Fr. Filas has asserted. In fact, the position of the letters UCAI as indicated by Filas probably precludes any possibility of the coin image having been produced by a coin of Pontius Pilate.”

Other Problems

In the October 1981 issue of The Augur, Wacks first disputed Fr. Filas’ Pilate coin theory on the basis that Pilate’s lituus coin was not minted until after August, 30 AD—well after the generally accepted date of the crucifixion (April, 30 AD).

“We can date the events surrounding the crucifixion to the day,” Wacks explained, “since the Last Super was actually the ritual Jewish Passover seder, and the exact date of Passover in 30 AD can be computed.”

The coin of Pontius Pilate were dated according to the regnal year of the Roman Emperor Tiberius, as was the custom. Tiberius, adopted son of Augustus Caesar, assumed the throne upon the death of Augustus in August, 14 AD. Thus, the years of Tiberius would have to be reckoned from August rather that the normal beginning of the Julian calendar in January. So, the first year of Tiberius ran from Aug, 14 AD, to July, 15 AD, and likewise with the following years. The time of the crucifixion would have fallen within the latter half of the 16th year of Tiberius’ rule, Wacks maintains.

The first coin issued by Pilate, Wacks continues, is dated LIS, representing the 16th regnal year. This small bronze ‘mite’ features three ears of barley and a simpulum (ceremonial ladle). The inscription surrounding the simpulum is identical to the legend around the augur’s wand (lituus) on the coins issued in the following two years. The reverse inscription honors the emperor’s mother, Julia, and this issue likely came to an abrupt end with her death in the year 29.

“The first of Pilate’s coins with the augur’s wand is dated LIZ (Year 19) and must have appeared some time after the start of Tiberius’ 17th regnal year in August, 30 AD—well after the crucifixion in April,” Wacks points out.

According to the Jerusalem Bible (1966) the date for the crucifixion was April 7, 30 AD. However, others dates are also supported and they range from 28-36 AD. Thus, the problem of the date of the Pontius Pilate lituus coins should be considered but it is not necessarily insurmountable, Wacks concludes. However, Wacks still considers the problem of the misplaced Shroud coin image inscription as critical.

Alternative Possibilites

After carefully examining highly magnified photographs (both two-dimensional and computer simulated three-dimensional) of the Shroud coin image, Wacks agrees that a pattern forms the letters CA. He also sees the vertical line following the CA that Fr. Filas calls an I, but Wacks feels that it could just as well be a portion of another letter such as P, with the right portion eaten away as is the case with most of the coin image’s design. In addition, Wacks believes that the letters preceding the CA, called a U by Fr. Filas, is crude enough to be another letter such as I.

The circumferential sequence ICAP (part of the word KAICAP, meaning Caesar) is found on several Prefect and Procurator coins: Coponius (6-9 AD), Ambibulus (9-12), Pontius Pilate, and Antonius Felix (52-60). Positioning the coins so that the letters ICAP appear in the approximate position for the Shroud photographs, Wacks notes that four of the five possibilities have the coin design but are incompatible with the pattern on the Shroud. The last possibility, coins of Coponius or Ambibulus, have a curved ear of barley that is somewhat similar in shape to a lituus, that is compatible with the letters, the design image, and most important, their relative positions. However, a portion of the inscription ICAP is split up so that it appears on the coins as ICA-P.

“It is conceivable that a portion of the barley design might extend high enough to cause the upright line following the ICA, but the chance of this happening is remote,” Wacks contends.

Grain of barley and inscription from coin of either Coponius or Ambibulus is superimposed on the Shroud’s coin image. This is just as good a fit as the Pontius Pilate coin, and doesn’t require searching for strange spellings and unusual positioning.

If the Shroud coin image was caused by a coin of Coponius or Ambibulus, it would cause no problems concerning the dating of the Shroud to the time of Jesus, Wacks points out, since coins circulated for decades and longer in the ancient world. The coins of Coponius and Ambibulus are among the most common of all Prefect and Procurator issues … and they were struck only about 20 years before Jesus’ crucifixion.

Using a similar technique of rotating a diagram of Fr. Filas’ second Pilate discovery coin—the one with the spelling error—so that the ICAP inscription overlaps those letters on the Shroud image, Wacks found that the two lituuses were badly out of alignment.

The second Pilate error coin has been superimposed over the Shroud coin image. He has rotated the position of the lituus 90 degrees counterclockwise from the way Fr. Filas has shown it.

Wacks concludes: “It is impossible to determine precisely the Judaean coin that might have caused the image on the Shroud since no one coin design—inscription, motif, and their respective positions—exactly matches the Shroud coin image. It is this vital third factor, positioning, that Fr. Filas neglected to take into account when he computed the mathematical probability of the coin image being the lituus coin of Pontius Pilate. If it is taken into account that the probability becomes infinitesimal.”

To prove his case, Wacks stresses, Fr. Filas must prove the existence of a lituus coin of Pontius Pilate with an error in spelling and an entirely new positioning of the inscription.

Wacks acknowledges the contributions of Robert Leonard Jr., whose articles helped to throw valuable light on this investigation.

© 2020-Mel Wacks