|

Plaque designed by Eugene Daub, produced by Jim Licaretz, unique bonded bronze. Portrait taken from Daguerreotype, D A U B. Approx. 10 inches. Medals sculpted and made in quantities of 90 bronze, 52 silver-plated, and 30 gold-plated by Customadecoins.com, 49 x 47 mm.

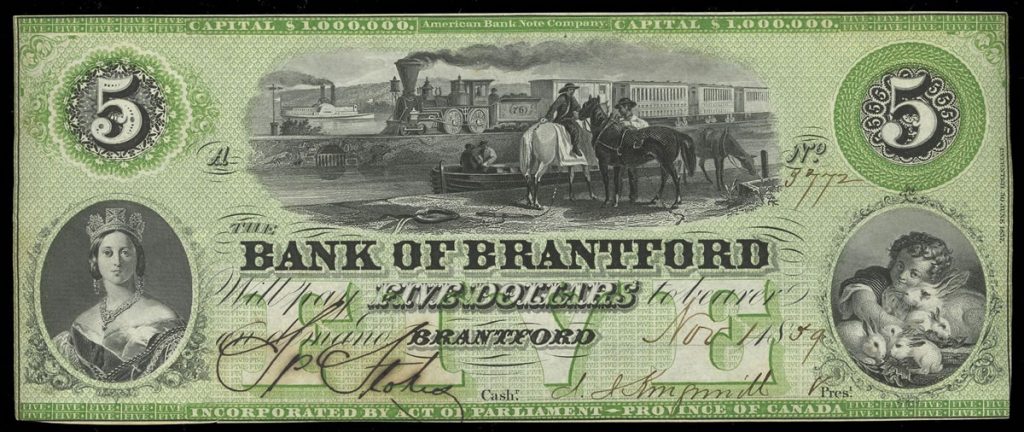

Solomon Nunes Carvalho was born in 1815 in Charleston, South Carolina into a Sephardic family. He was a talented artist, and a painting he made at age 25, “Child with Rabbits,” would later be incorporated into national bank notes of a number of U.S. state banks, and even a Canadian bank (pictured).

Carvalho was a board member of the Philadelphia Hebrew Education Society from 1849–1850, and the following year, he became a member of New York’s historic Congregation Shearith Israel.

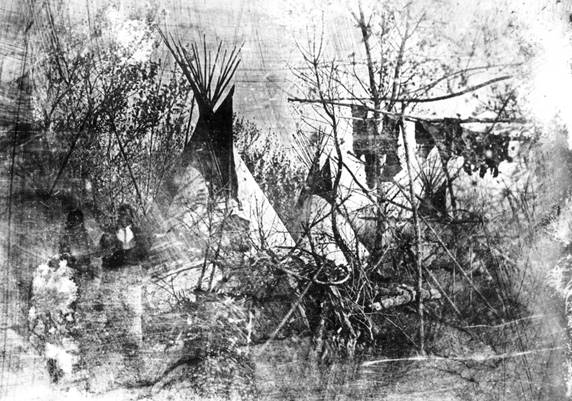

In 1853, Colonel John C. Frémont, invited the young artist to accompany him as he attempted to prove that a “central route” near the thirty-eighth parallel would be the best path for a planned transcontinental railroad. During the trip, despite the frigid weather which made chemical combinations difficult, Carvalho made near daily portraits of expedition members, the Native Americans they met, and the landscape. Solomon Carvalho would nearly die on that trip of scurvy, starvation and frostbite. Carvalho later recovered enough to reach Los Angeles, California and its small Jewish community, helping them organize the Hebrew Benevolent Society.

Tragically, all but one of the near 300 daguerreotypes taken by Carvalho during the Frémont expedition were lost in a fire. Solomon Carvalho published his diary of the five-month journey, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West; with Colonel Frémont’s Last Expedition (1860).

After the American Civil War, Carvalho moved his family to New York City, but cataracts impaired his continuing portrait work by 1869, and would ultimately blind him. He became an inventor, and received two patents for steam superheating in 1877 and 1878.