|  |

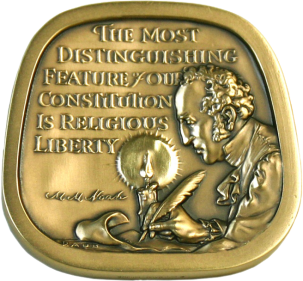

Mordecai Manuel Noah medal designed by Eugene Daub, struck by Medallic Art Company in quantities of 120 bronze, 65 silver-plated bronze, and 27 gold-plated bronze. Obverse: Portrait, MORDECAI M. NOAH 1785-1851. EU. DAUB. Reverse: Noah writing by candlelight, THE MOST DISTINGUISHING FEATURE of OUR CONSTITUTION IS RELIGIOUS LIBERTY, M. M. Noah (signature), DAUB. 49 x 47 mm.

Mordecai Manuel Noah was born in Philadelphia, on July 19, 1785. He was the first-born son of Manuel Noah, an immigrant from Mannheim, Germany, who had served in the American Revolutionary War, and Zipporah Phillips, daughter of Jonas Phillips and Rebecca Machado, whose father had served as hazzan (cantor) of the Shearith Israel Congregation of New York. Though three of his grandparents were Ashkenazi, Noah stressed his Sephardi identity as a public servant, Noah served as a Major in the New York Militia, Consul to the Kingdom of Tunis, sheriff of New York and surveyor of its port, and judge in its court of General Sessions. In his lifetime, Noah was editor of half a dozen newspapers. In the Jewish community, Noah served as its chief orator, delivering the major addresses at its important communal gatherings. To Americans he was the representative Jew; to Jews, he was the quintessential American.

Noah wrote to Secretary of State James Monroe in 1811, that his appointment to a consulship would “prove to foreign powers that our government is not regulated in the appointment of their officers by religious distinction.” But unfortunately, even after he had arranged for the freedom of Americans held captive by Barbary Coast pirates, Noah’s position as Consul to the Kingdom of Tunis was terminated by Monroe, who stated: “At the time of your appointment, as Consul to Tunis, it was not known that the religion which you profess would form an obstacle to the exercise of your Consular functions.” Noah’s response, in part, was: “My dismissal from office in consequence of religion … may hereafter produce the most injurious effects establishing a principle, which will go to annihilate the most sacred rights of the citizen.”

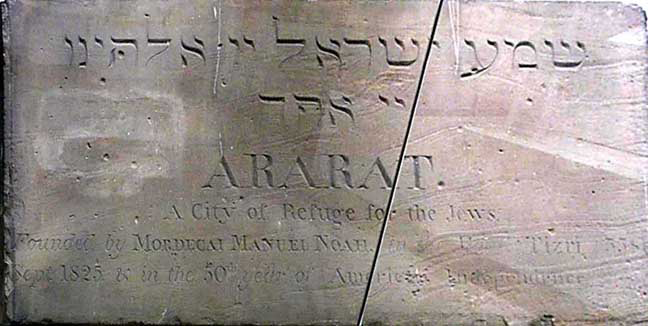

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, America’s greatest need was for immigrants. Thus, in Buffalo, New York on September 15, 1825, Noah dedicated Ararat as “A City of Refuge for the Jews.” Accounts of the Ararat ceremony appeared in newspapers throughout the United States and in England, France, and Germany as well. The event presented the Jews as the most desirable citizens a nation could want — able, ambitious, productive, and loyal. To the Jews of the Old World, it portrayed what kind of country America was for the Jews. America’s most prominent Jew proclaimed a Jewish state on American soil and welcomed his brethren to settle it.

The ceremonies included the laying of the cornerstone, with its Hebrew prayer “Sh’ma Yisrael Adonai Elohaynu Adonai Echad” (Hear O Israel the Lord is God the Lord is One), and English inscription: “Ararat, a City of Refuge for the Jews, founded by Mordecai M. Noah in the Month of Tishri, 5586 (September, 1825) and in the Fiftieth Year of American Independence.” The cornerstone is on now on display at the Buffalo Historical Society.

While Noah’s efforts to establish a Jewish homeland in the United States failed, in 1837 he called for: “The Jewish people must now do something for themselves … Syria [i.e., Palestine] will revert to the Jewish nation by purchase … Under the co-operation and protection of England and France, this reoccupation of Syria … is at once reasonable and practicable.”

Noah wrote these prophetic words a half-century before Theodor Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat, and more than a century before the establishment of the State of Israel.

Bibliography: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, 1991).