|

|

|

Important New Discoveries about the

First American Jewish Medal

By Mel Wacks, Director of the Jewish-American Hall of Fame Division

of the American Jewish Historical Society

Originally published in The Medal, the magazine of the British Art Medal Society

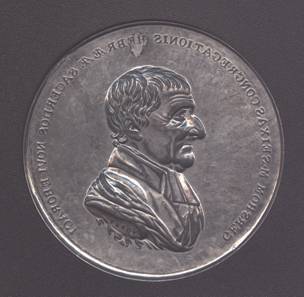

One of the American Jewish Historical Society’s many prized possessions is a medallic die featuring a portrait of Gershom Mendes Seixas, “the first recorded American Jewish medal”1. The legend reads: “GERSHOM M. SEIXAS CONGREGATIONIS HEBRAEAE SACERDOS NOVI EBORACI”2 with the name of the medalist “FüRST” on the truncation of the bust. The commonly held view about this historic medal was stated by Chris Neuzil3: “Only modern uniface strikes from this die, which is in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, are known (fig. 1). Friedenberg states that this “excessively rare homage (was made) on the death in 1816 of Gershom Mendes Seixas.”4 However, recent research by the author has revealed that long held beliefs about the Seixas medal are in fact mistaken.

Figure 1. Modern uniface strike from the die in the

collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.

Born in New York City on January 14, 1745, Seixas became the minister of Shearith Israel, the Spanish-Portuguese Congregation in 1768, and occupied the rabbinate for a total of about 50 years. In 1776, at the outbreak of the American Revolution, he immediately espoused the patriot cause, and it was largely due to his influence that the Jewish congregation closed its doors rather than continue under British rule. Seixas fled first to Connecticut and then Philadelphia in 1780, where he served as minister and helped establish Congregation Mikveh Israel. He returned to New York on March 23, 1784 to resume his former position. At times, Seixas also served as the community's mohel (circumciser), teacher, and shochet (ritual slaughterer). His first wife Elkalah Myers-Cohen gave birth to four children; after her death Seixas married Hannah Manuel and they had eleven children. The Papers of the Seixas Family are in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society.

In 1784, Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas was named as a Regent of Columbia College, and subsequently served as a Trustee from 1787 until 1815. When the college was incorporated, Seixas' name appeared in the charter as one of the incorporators. Seixas fell seriously ill in 1813, lingering on for several years, until July 2, 1816, when he died. His funeral was held in the Mill Street Synagogue of Shearith Israel, and he was eulogized by Jacob de la Motta, a leader of the Congregation: “Seixas, from an early period in life, was endowed with no commonplace intellect…pursuing undeviatingly the most correct deportment; admired by all; esteemed alike in every grade of society…. (He prosecuted) uninterruptedly a line of conduct that obtained for him the love, respect, and esteem of all sects.”

It is commonly held5 that the die was made in 1816 by Columbia College as a memorial to its long-time trustee, Gershom Mendes Seixas. But this is not true. In the Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society6 it states that on Feb. 7, 1812 " M*- Seixas presented an impression in paper of a die cut by Fürst in this city (Philadelphia), of his father Gershom M. Seixas, on account of its superior execution." Thus the die was made sometime before this date, which was nearly 4½ years before Seixas died.

The die was produced by the Slovakian-Jewish engraver Moritz Fürst, who was 26 years old when he came to America in 1807. Fürst was eventually given commissions for die-engraving by the fifteen-year-old United States Mint, but he was not given the post of chief engraver, which he had expected. Among the best-known of Fürst’s medals are the series of twenty-seven commemoratives honoring naval and military heroes of the War of 1812—including handsome pieces still sold by the U.S. Mint today. In addition, he created the official presidential portrait medals of James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and Martin Van Buren. Neuzil indicates that it is quite possible that the total number of dies attributable to Fürst while he was in America (1807-1840) is perhaps 113 or even more, but just 5 can be dated to 1812 or earlier7. Thus the Seixas die is one of Fürst’s earliest such works in America. It may have been commissioned by the Seixas family (a member of which evidently had access to the die), or just produced as a speculative venture by Fürst, as were other dies.

The silver medal in the Columbia University Archives, which has been all but forgotten by modern researchers, was actually a gift from Judaica collector Harry Friedman, as noted in letter dated November 30, 19338. This medal was published in 19629, where it was called “bronze.” And this leads to another remarkable rediscovery. The medal in the Columbia University Archives was produced from the die that was extant in 1812 and that is in the possession of the American Jewish Historical Society – but it has an added engraved inscription above the portrait, reading: “BORNJANUARY 14TH, 1745 GERSHOM MENDES SEIXAS DIED JULY 2ND, 1816” (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Obverse of Columbia University’s

medal with inscription made after Seixas’ death.

Upon close inspection, it is confirmed that the Columbia medal was made from the die in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society. However, the back of Columbia’s Seixas medal, pictured here for the first time (fig. 3), was stamped from a mirror-imaged die that had many subtle differences. For instance, the lettering AEAE (in HEBRAEAE) uses flat bottomed E’s on the front and rounded bottoms on the back; and while these front letters are sharp, the back letters are double struck. Also, Seixas’ eyebrows are far more textured on the front than the back. Just such a uniface silver “shell” medal wasmade by Fürst, depicting a bust of George Washington atop a broad pedestal, as initially described in an 1817 catalogue10

Figure 3. Reverse of Columbia University’s “shell” medal.

To summarize: Moritz Fürst created a die in Philadelphia for a portrait medal honoring Gershom Mendes Seixas some time before February 7, 1812. At least one silver “shell” medal was struck from this die and it was then engraved with Seixas’ name and dates of birth and death after July 2, 1816. Over a century later, Harry Friedman acquired the medal, and subsequently contributed it to Columbia University in November, 1933. There is no evidence that this medal was authorized by Columbia, as scholars have presumed. Finally, the author personally knows that a few uniface pieces were made in the 1970s by Medallic Art Company from the original die in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society -- one silver strike is in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society and one lead impression is in the author’s collection.

Mel Wacks holding original Seixas die9 at the Mel Wacks holding original Seixas die9 at the

headquarters of the American Jewish His-

torical Society, 2017. Photo by Tanya ElderI want to thank Jocelyn K. Wilk, Public Services Archivist at Columbia University Archives, and medallic art historian Dick Johnson for their invaluable research assistance.

Notes

- Daniel Friedenberg, Jewish Minters and Medalists (Philadelphia,1976), p. 67.

- Gordon Hume, What to See in England, 1903, www.authorama.com: “The city of York was originally called Eborac by the British in ancient times and before that it was the Eboracum of the Romans, who made it an imperial colony.” The inscription “NOVA EBORAC” can be found on copper coinage dated 1787 for use in colonial New York, and even on the famous Brasher Doubloons made in

the same year.

- Chris Neuzil, A Reckoning of Moritz Fürst’s American Medals, in The Medal in America Volume 2 (New York, 1999), p.106.Daniel Friedenberg, p. 70.

- David Bridger Ph.D., editor, The New Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1962),

p. 438; Robert Wilson Hoge, A Doctor for All Seasons: David Hosack of New

York, in The American Numismatic Society Magazine (New York, Spring

2007), p. 53.

- Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Compiled by One of the Secretaries, from the Manuscript Minutes of its Meetings from 1744 to 1838 (Philadelphia, 1884), p.433.Chris Neuzil, p. 23

(Fig. 2).

- From Philip M. Hayden, Secretary, Columbia University in the City of New

York to James T. Grady, 505 Journalism, in which he states in part: “(Seixas)

was a leading Hebrew Rabi (sic) of his period, and was a member of the

governing board of Columbia College, as one of the Regents of the State of

New York from 1784 to 1787 and as Trustee from 1787 to 1815. The medallion is in silver and in relief, without any reverse, and signed, Furst, apparently the name of the sculptor. The President thinks that both the Times and the Alumni News might use a photograph of the medallion.”

- David Bridger Ph.D., editor, p. 438.

- Chris Neuzil, p.96-7.

- The original die was donated (bequeathed?) to the AJHS in 1935 by a member, Miss Serena Kursheedt (1850-1935). Miss Kursheedt’s father was Asher Kursheedt (1808-1893), whose mother was Sarah Abigail Seixas (1778-1854)—daughter of Gershom Mendes Seixas (1746-1816).

Figures

- Fürst: Gershom Mendes Seixas, 1970s, lead impression of original die in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, 80mm. (image 68mm.),

Mel Wacks Collection, California (Photo: Mel Wacks)

- Fürst: Gershom Mendes Seixas, c.1816, obverse (front), silver, 68mm.,

Columbia University Archives, New York (Photo: With permission of the University Archives, Columbia University in the City of New York)

- Fürst: Gershom Mendes Seixas, c.1816, obverse (back), silver, 68mm., Columbia University Archives, New York (Photo: With permission of the University Archives, Columbia University in the City of New York)

Addendum

While Fürst’s Seixas medal was evidently the first American Jewish medal struck in America, famous silversmith Myer Myers actually made an engraved circumcision medal about 50 years earlier! You are invited to read “A New Candidate for the First American Jewish Medal.”

|